Czeching Out Prague’s Top Day Trips

By Rick Steves

Few cities can match Prague's over-the-top romance, evocative Old World charm…or its tourist crowds. To escape the masses and experience more of the real Czech Republic, take a bus or train ride outside of the city to see some of the many worthwhile sights just beyond. My three favorites are a rich medieval town, a sobering concentration camp memorial, and a grand Czech castle.

Kutná Hora, a beautifully preserved and down-to-earth town, is just a one-hour direct train ride from Prague. With a current population of just 20,000 it can hardly be categorized as a "second city" to Prague, but it was considered the second city of Bohemia in the 17th century. Kutná Hora sits on top of what was once the world's largest silver mine and, in its heyday, much of Europe's standard coinage was minted here. At the town's Czech Museum of Silver, you can join a tour and spelunk in the former miners' passages that run beneath the town center.

In addition to financing much of Prague's grand architecture, the glittering silver deposits also paid for Kutná Hora's opulent Gothic cathedral, St. Barbara's, dedicated to the patron saint of mining. Its dazzling interior celebrates the town's sources of wealth, with frescoes featuring mining and minting.

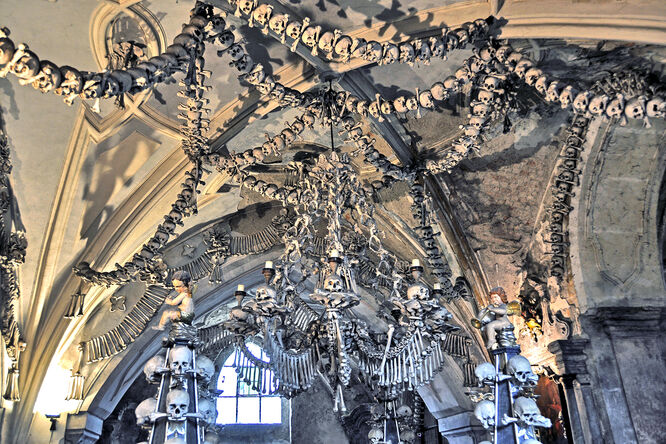

Kutná Hora's most popular sight is actually on its outskirts, in the suburb of Sedlec: the evocative and offbeat bone church, within a serene graveyard. Unassuming from the outside, the 16th-century Sedlec Ossuary is filled with the bones of 40,000 people. The raw material inside was provided by 14th-century plagues and 15th-century wars. Its chandelier supposedly includes at least one of every bone in the human body. Neat, 20-foot-tall pyramids decorate the walls and ceilings, and giant chalices made of bones flank the stairwell.

To explore more recent Czech history, ride the bus to the walled town of Terezín, just one hour from Prague. Built in the 1780s with state-of-the-art, star-shaped walls designed to keep out the Prussians, it became a horribly overcrowded Jewish ghetto under Hitler. Ironically, the town's medieval walls, originally meant to keep Germans out, were later used by Germans to keep the Jews in.

The various museums, memorials, and points of interest of the Terezín experience are spread over a large area in two distinct parts: the walled town, which today feels like a workaday, if unusually tidy, Czech town, with a tight grid plan hemmed in by its stout walls; and (a half-mile walk east, across the river) the Small Fortress, which had been a Gestapo prison camp for political prisoners of all stripes (including non-Jewish Czechs).

Here, in a supposedly "self-governed Jewish resettlement area," Jewish culture seemed to thrive, as "citizens" put on plays and concerts, published a magazine, and raised their families. But it was all a carefully planned deception. As the Nazis' model "Jewish town" for deceiving Red Cross inspectors, Terezín fostered the illusion that its Jewish inmates lived relatively normal lives — making the sinister truth all the more cruel. When I explore memorials such as this one, I always ponder the message "Forgive, but never forget."

Other day-trip opportunities from Prague include several castles. The Neo-Gothic Konopiště Castle, 30 miles south of Prague, has some captivating stories to tell about its former inhabitants, including Archduke Franz Ferdinand — the heir to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, whose assassination sparked World War I.

Inside Konopiště are halls upon halls of hunting trophies, paintings of royal relatives, and photographs of Franz Ferdinand and family's travels. More importantly, the castle stands as a reminder of what his assassination (chillingly illustrated by items displayed inside the castle) meant for Europe — the end of the age of hereditary, divine-right empires, and the dawn of Europe as a collection of nationalistic, democratic nation-states. Historians get goose bumps at Konopiště, where if you listen closely, you can almost hear the last gasp of Europe's absolute monarchs.

You can see Franz Ferdinand's dressing room (with his actual uniform and his travel case all packed up and ready to go), his private study (which feels like he just stepped away from his desk for a cup of coffee), and — in the final room — a glass display case containing the dress his wife Žofie was wearing when she was also shot that fateful day in Sarajevo. Down the hall are the royal couple's death masks, Franz Ferdinand's bloody suspenders, and the very bullet that ended Žofie's life.

Ninety percent of tourists who visit the Czech Republic see only Prague. But if you venture outside the capital, the country offers a little of everything for the traveler. Traditional towns and villages? Check. A friendly and gentle countryside? Check. Grand castles? Czech, Czech, and Czech.