Italy’s Ravenna: Once Powerful, Still Glorious

By Rick Steves

Ravenna is on Italy's tourist map for one reason: its 1,500-year-old churches decorated with best-in-the-West Byzantine mosaics. While locals go about their business, busloads of tourists slip in and out of this town near the Adriatic coast to bask in the glittering glory of Byzantium, the eastern Roman Empire.

Imagine…it's AD 540. The city of Rome has been looted, the land is crawling with barbarians, and the Roman Empire is crumbling fast. Into this chaos comes the emperor of the East, Justinian, bringing order and stability — and an appreciation for mosaic art.

As the westernmost pillar of the Byzantine Empire, Ravenna was a flickering light in Europe's Dark Ages. To fully appreciate the mosaics in its ancient churches, bring your binoculars and take in every last detail. Sit in a wooden pew, front and center, and feel yourself transported to a spiritual world.

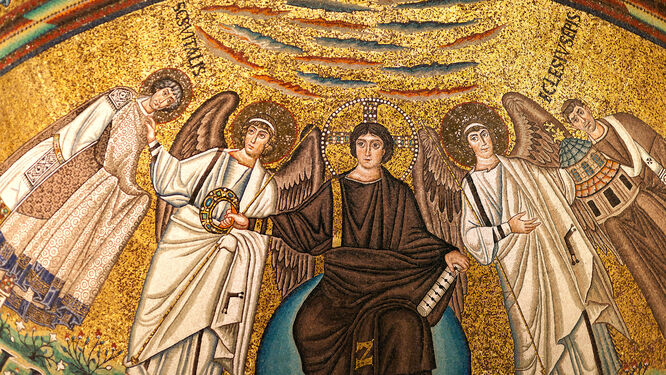

My favorite church in Ravenna is Justinian's Basilica di San Vitale. The building's octagonal shape — very much an Eastern style — actually inspired the construction of the magnificent Hagia Sophia church built 10 years later in Constantinople (now Istanbul). While it's impressive enough to see a 15-centuries-old church, it's even more exciting to see one decorated with brilliant scenes in marble and glass mosaics — each chip no bigger than a fingernail. High above the altar, Christ is in heaven, overseeing creation. To the left of the altar, running things here on earth, is Emperor Justinian — sporting both a halo and a crown to show he's leader of the church and the state. On the opposite wall is his wife, Theodora. A former Constantinople showgirl, she ruled alongside her emperor husband in their lavish court.

The mosaics on the walls and ceilings of San Vitale sit at a tipping point in time, when European art shifted from the style of ancient Rome to that of the Middle Ages. Above the altar, Christ is beardless, in the manner of the ancient Romans, but nearby, decorating an arch, is a bearded Jesus, the standard medieval portrayal. Yet both scenes were created by artists of the same generation.

The humble-looking little Mausoleum of Galla Placidia has the oldest — and to many, the best — mosaics in Ravenna. The little light that sneaks through its thin alabaster windows brings a glow and a twinkle to the very early Christian symbolism that fills the little room. Pre-dating Justinian, the mosaics here are purely ancient. Even Jesus is dressed in gold and purple, like a Byzantine emperor.

Another spot to gaze upon the sparkling mosaics of Ravenna is at the austere Basilica di Sant'Apollinare Nuovo, decorated with two huge and wonderfully preserved decoration above both sides of the nave. The tiny colored glass and gold-leaf mosaic pieces here are practically as brilliant and beautiful as they were in Justinian's time.

Justinian turned Ravenna into a pinnacle of civilization. After 200 years, however, the Byzantines got the boot, and Ravenna eventually melted into the background, staying out of historical sight for a thousand years. Today the local economy is stoked by a big chemical industry, the discovery of offshore gas deposits, and the city's booming popularity as a cruise-ship stop.

Ravenna is a doable, though long, day trip from Venice or Padua (about three hours by train each way) and worth the effort for those curious about old mosaics. The key sights are all easily walkable from the train station, but this is a fun city to do by bike. A handy bike-rental place is right next to the station. (I've long enjoyed doing my guidebook-research rounds in Ravenna on two wheels.)

At the town's center is Piazza del Popolo, created by Ravenna's Venetian rulers in the 15th century. A river once flowed here, but it silted up and became infested with mosquitoes. (Dante died here of malaria.) In the centuries since it was paved over, the people of Ravenna have treated this spot as their communal living room. Today, in the shadow of Venetian facades, it's a fine place to join the old guys on benches, watching locals parade by, quite at ease about sharing their town with the world's most exquisite mosaics.

So much sightseeing greatness hides in the shadows of Europe's more popular tourist attractions. While Ravenna can't hold a candle to nearby Venice, it still gives off its own glittering light.